In her latest blog post, Dr Caroline Leaf attempted to tackle the complex topic of Alzheimer disease.

Alzheimer disease is an important topic. It’s the most common progressive neurodegenerative disease worldwide and accounts for 60 to 80% of dementia cases. It causes a spectrum of memory impairment from forgetting where the car keys are through to forgetting to eat or drink. According to the 2018 report by the Alzheimer’s Association, an estimated 5.7 million Americans are diagnosed with Alzheimer dementia, costing their economy $277 billion in 2018 [1]. That’s a staggering economic cost, but the human cost is higher. Alzheimer’s exacts a great emotional toll on someone’s family and friends, both in terms of carer stress, and in seeing the person they love gradually slip away as the disease slowly erodes their personality until there’s nothing left.

There are two main forms of Alzheimer disease, an early onset type which accounts for about 5% cases, and a late onset type which accounts for the rest. Early onset Alzheimer disease occurs before the age of 65. It’s also called Familial Alzheimer disease because it’s caused by one of three autosomal dominant genes (if you have a copy of the gene, then you will get the disease). Late onset Alzheimer disease, as the name suggests, occurs late, after the age of 65. It’s more complex and is associated with a mix of both genetic, lifestyle and environmental risk factors.

The neurobiology of Alzheimer disease is complicated. Essentially, the symptoms of Alzheimer disease result from the death of too many nerve cells in the parts of the brain that manage memory and planning, but scientists are still trying to establish exactly why the nerve cells die. There are a number of pieces of the jigsaw already in place.

For example, scientists know that amyloid plaques and neurofibrilliary tangles are part of the disease process. These result from genetic changes to a number of enzymes which are critical to the nerve cells maintaining their structural integrity. It was first thought that these particular cell changes were critical factors to the nerve cells dying, but there are a number of other contributing factors that are also involved, such as changes to the metabolism of the nerve cells [2], inflammation of the brain, changes in the brain’s immune function, and changes to nerve cell responses to insult or injury (technically, endocytosis and apotosis, just in case you were wondering)[3].

In fact, it may be that the plaques and tangles are not the cause of the damage but are simply present while the other causes such as neuro-inflammation are doing all of the damage in the background. This is possible as there are a small group of people that have cellular changes of plaques and tangles, but who do not have the clinical signs of dementia. This was one of the discoveries in the Nun Study. We’ll talk more about the Nun Study later in the post.

Whether it’s the plaques and tangles doing the damage or not, most of these changes are happening well and truly before a person ever shows any symptoms. In fact, by the time a person has some mild cognitive impairment, the plaques have reached their maximum level and the tangles are close behind. This makes Alzheimer disease clinically challenging. It would be ideal if we could start treatment early in the course of the disease before the damage has been established, but right now, the fact is that by the time a person is showing signs of memory loss, the damage to the cells is already done.

This begs the question, can we reduce our risk of Alzheimer disease? There’s no good treatment for it, and even if there was, prevention is always better that cure. So what causes Alzheimer disease in the first place?

There are a number of factors which contribute to the development of Alzheimer disease, some of which we can change, but some of which we can’t.

Unmodifiable Risk Factors

- Aging

Aging is the greatest risk factor for late onset Alzheimer disease. The older you get, the more likely you are to get the disease. Statistically, late onset Alzheimer disease will affect 3% of people between the ages 65–74, 17% of people aged 75–84 and 32% of people that are aged 85 years or older [1].

That’s not to say that Alzheimer disease and normal aging are the same. Everything shrinks and shrivels as you get older and the brain is no exception. And it’s true that Alzheimer disease and normal aging share some similarities in the parts of the brain most affected. However, these occur much more rapidly in Alzheimer disease compared to normal aging [4].

So, while aging is a necessary and significant risk factor for late onset Alzheimer disease, aging alone is not sufficient to cause Alzheimer disease.

Also, normal aging of the brain is not dementia. And forgetting things is not dementia. Everyone forgets things. My teenage children forget lots of things I tell them. They don’t have dementia. Getting old doesn’t mean getting senile. Some elderly people remain as sharp as a tack until the rest of their body gives up on them.

- Genetics

There are a number of genes which have been associated with Alzheimer disease.

As I alluded to earlier, early onset Alzheimer disease is strongly hereditary, with three different autosomal dominant genes that lead to its development. They are known as APP, PSEN1and PSEN2genes[5]. The APPgene encodes for a protein is sequentially cleaved into peptides which then aggregate and form amyloid plaques. PSEN1and PSEN2encode subunits of one of the enzymes which breaks up the amyloid protein. Then there is a problem with one of the genes, the breakdown of the amyloid proteins is limited and the amyloid plaques start to accumulate at a much earlier age.

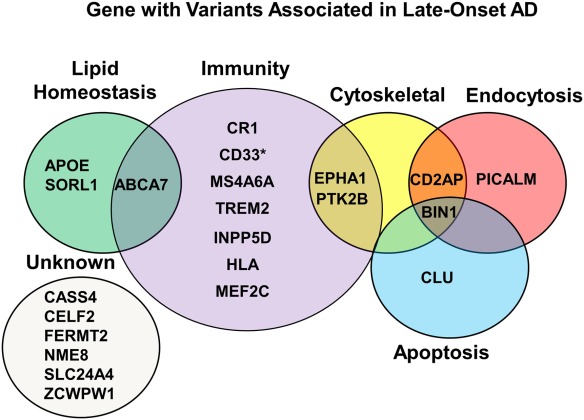

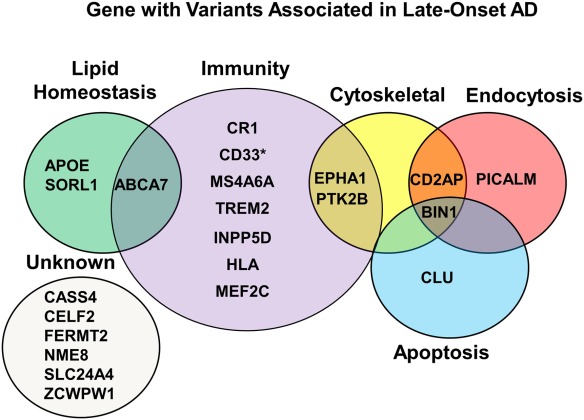

For late onset Alzheimer disease, there are 21 associated gene variants which are either splice variants, or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and while they don’t cause Alzheimer disease, they increase the risk when they interact with other risk factors. Each of the genes is important to one of the five main biological processes that influence the cellular structure and function of nerve cells.

(taken from Eid A, Mhatre I, Richardson JR. Gene-environment interactions in Alzheimer’s disease: A potential path to precision medicine. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;199:173-87)

The risk that any of these genes confers for developing Alzheimer disease is ultimately dependent on other risk factors, but one of the most well-known of the genes related to Alzheimer disease is the gene APOE4. Apolipoprotein (APO) is a lipid carrier and is significantly involved in cholesterol metabolism. In humans, it’s expressed as either E2, E3 or E4 variants. The E4 variant has a much lower affinity for lipoproteins than its siblings, and if you have the APOE4, you have much poorer cholesterol metabolism – in your liver cells and in your brain cells. Again, this fact may not seem important now but it will be more important later in the post.

If you inherit a copy of the APOE4 gene from your mother and your father, you have an 8 – 12 times greater risk of developing Alzheimer disease than another person without both copies of the gene.

- Family history

So if there are genes that can send your risk of Alzheimer disease through the roof, then it follows that having a family history of Alzheimer disease is a risk factor.

Individuals who have a first-degree relative, such as a parent, brother or sister who was diagnosed with Alzheimer disease are predisposed to develop the disease with a 4–10 times increased risk, compared to individuals who do not [6].

Of course, family history is not all to do with genetic risk factors, but it’s usually a combination of both genetics and share home environment between parents and siblings, hence why the risk conferred is not as high as APOE4, but is still very high.

- Ethnicity

Early studies suggested that Alzheimer disease was more common in certain races, although the thought was that the risk was related to social and economic conditions common to those races, and not to specific genes.

Recently, better genetic studies have linked a few genes with some races. For example, there is a link with genes such as APOE4 which is twice as likely in African-American’s than other races, or a higher rate of mutations in the CLU gene amongst Caucasians [7].

- Gender

There is a strong gender difference for Alzheimer disease. Overall, women are twice as likely to develop Alzheimer disease than men are.

There are a few possible reasons why this might be so. Inflammatory mechanisms might play a part, as does the function of the part of the cell called mitochondria. Hormonal differences might make some differences as well, specifically in relation to the oestrogen or the cell receptors for oestrogen.

There are also some gender differences in the way other genes play out. For example, it’s known that women with the APOE4 gene will experience a faster cognitive decline than men with the same gene [8]. Sorry ladies.

Modifiable Risk Factors

So whether we like it or not, there are some risk factors for Alzheimer disease that we can’t change. We can’t change our genes, our race, or our gender. We can’t get any younger either.

What about the risk factors for Alzheimer disease that we might be able to change?

- Education

There’s some correlation between how much education someone has had and their risk of Alzheimer disease.

A meta-analysis by Larsson and colleagues which examined studies through to mid 2014 reported a statistical association of low education attainment (less than or equivalent to primary school) and increased Alzheimer disease risk. For those with a primary education or lower, the risk of Alzheimer disease was 41 to 60 percent higher compared to someone who had better than primary school. In a separate study, those who completed higher education (university level or above) had a lower risk of Alzheimer disease compared to those without higher education – approximately 11 percent per year of completed university level education [9]. There is some evidence that Alzheimer disease patients with higher education have a bigger part of the brain related to memory which is thought to be protective (if you have a bigger memory part of the brain, it will take longer to shrink in Alzheimer’s).

Two points to think about here. First, these studies are not demonstrating cause and effect. They don’t definitely prove that learning more stuff protects you from Alzheimer disease. The statistics could simply reflect that people with the ability to learn more information had more robust nerve cells and connections to start with.

Also, while a 60 percent increase in risk sounds high, remember that the APOE4 gene carries a 1200 percent increased risk. Comparatively speaking, the effect of education is actually quite small compared to other risk factors.

- Metabolic factors

Remember how we talked before about cholesterol and the APOE4 variants? If you have both copies of the APOE4 gene, your liver cells and your brain cells aren’t good at handling lipoproteins.

Your liver cells are important in regulating your blood cholesterol. Your brain cells are important for handling the amyloid proteins and lipids for making new nerve cell branches.

With APOE4, the liver doesn’t handle the blood cholesterol properly and you end up with high cholesterol and cholesterol plaques in the coronary arteries. When the brain cells don’t handle cholesterol properly, there is an increase in plaques and tangles and neuro-inflammation which increases the risk of Alzheimer disease.

At one stage, researchers thought that having a higher blood cholesterol was linked to Alzheimer disease but further research has shown that the results are inconsistent – some studies show a link while others show no link at all. So all in all, there’s probably no cause and effect relationship with cholesterol and Alzheimer disease. In fact, there’s some suggestion that high cholesterol is not a causative factor, but rather the result of Alzheimer disease [10] or simply a correlation, related to an underlying genetic or metabolic disorder which is common to both conditions.

Blood sugar was also considered to be a key factor for Alzheimer disease. The Rotterdam Study conducted in the 1990s linked diabetes to Alzheimer disease [11], while a more recent nationwide population-based study in Taiwan showed that there was a higher incidence of dementia in diabetic patients [12].

While it may be that high blood sugar leads to Alzheimer disease, more recent research has suggested that there is a two-way interaction between Alzheimer disease and diabetes – diabetes increases the risk of Alzheimer disease, but Alzheimer disease increases the risk of diabetes. Other scientists have recognised that there is a metabolic disease with overlapping molecular mechanisms shared between diabetes and Alzheimer disease. These molecular mechanisms relate to less total insulin and higher insulin resistance, a mix of the pathologies seen in type 1 and type 2 diabetes – hence why one scientist called the underlying metabolic disorder “type 3 diabetes” [13].

So while cholesterol and blood sugar are linked to Alzheimer disease, it’s not clear whether aggressively lowering them would decrease the risk of Alzheimer disease or not.

- Lifestyle choices (food and exercise)

If it’s not clear how much our metabolic factors have on our Alzheimer disease risk, what about the food we eat?

There’s some evidence that having a healthy lifestyle reduces the risk of Alzheimer disease, but it’s not known what factors of lifestyle are the most important. There was a study done on residents of New York City, and those who had a strict adherence to a Mediterranean diet and who participated in physical activity decreased their Alzheimer disease risk by about 35 percent [14]. That’s promising, but while there have been lots of studies into various aspects of diet and Alzheimer disease, it’s not clear what exactly works and why [15].

We can’t dismiss lifestyle changes, but more research is needed.

- Others

Smoking and alcohol are usually implicated in everything bad, and one would expect that their role in Alzheimer disease would be the same. So it surprised everyone when one meta-analysis declared that smoking had a protective effect on Alzheimer disease.

The result sounded too good to be true and it probably is. It’s likely that either smoking killed off all of the weaker people and only left those “healthier” smokers for the study population, or that smokers would have gotten Alzheimer disease had it not been for the fact that the smoking simply killed them off first.

Moral of the story – don’t take up smoking in the hope it will protect you from Alzheimer disease. Even if it did, the lung cancer and emphysema will get you first.

Alcohol, on the other hand, was fairly neutral in broad population studies. That may be because the benefits of a small amount of wine drinking were being averaged out by the harmful effects of drinking too much hard liquor. When the amount and type of alcohol drunk was separated out, there’s some evidence that a little bit of wine infrequently is somewhat preventative of Alzheimer disease [16].

Air pollution is a potential risk factor for Alzheimer disease. It’s thought that the high exposure to chemicals and particulate matter in the air increases neuro-inflammation and death of the nerve cells leading to Alzheimer disease. In a case-control study in Taiwan, individuals with the highest exposure to air pollution had a 2 to 4-fold increased risk in developing Alzheimer disease [17].

There are similar concerns about the risk of pesticide exposure and Alzheimer disease, although there are often a lot more confounders within the research itself, which makes the associations somewhat weaker. Still, evidence is generally supportive of a link between pesticide exposure and the development of Alzheimer disease.

Risk factors – what can we learn?

In summary, there are a lot of different risk factors which are involved in Alzheimer disease, some of which can be influenced, and some which cannot.

Alzheimer disease is not a homogeneous disease that can be treated with one specific drug, but rather AD presents as a spectrum, with complex interactions between genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors. So to really understand a person’s risk for Alzheimer disease, the interactions of these risk factors need to be understood which actually makes things exponentially harder.

That means that anyone telling you to eat this, or learn that, or do my program to reduce the risk of Alzheimer disease clearly doesn’t understand just how complicated Alzheimer disease is and has oversimplified things way too much.

Which brings us back to Dr Leaf and her blog.

I was surprised that Dr Leaf even tried to broach the subject of Alzheimer disease, because diseases like Alzheimers disprove her most fundamental assumption. Dr Leaf has always taught that the mind is separate to the brain and is in control of the brain. But if that were the case, the brain changes in Alzheimer disease would make no difference to a person’s cognition and memory. Yet Dr Leaf admits throughout the entire post that the brain changes in Alzheimer disease do cause changes in the mind.

Dr Leaf can’t have it both ways. Real cognitive neuroscientists don’t constantly contradict themselves, tripping themselves up on the most fundamental of all facts. Dr Leaf needs to correct her most fundamental of all her assumptions and admit that the mind is a product of the physical brain and does not control the brain.

Dr Leaf also needs to stop exaggerating her “research and clinical experience”. She’s quick to point over every time she opens her mouth that she has decades of research and clinical experience, but such repeated and unjustified exaggeration is just another form of lying. Her research was an outdated and irrelevant PhD in the late 1990’s, based on a theory which she tested on school children. Her limited clinical experience was as a therapist for children with acquired brain injuries.

Alzheimer disease affects the other end of the age spectrum and has nothing to do with acquired brain injury. It is the absolute polar opposite of Dr Leaf’s already limited research and clinical experience. Dr Leaf is like an Eskimo trying to build an igloo in the Sahara.

Dr Leaf’s credibility on the subject quickly evaporates with her introductory caution:

Before we go into too much detail, I want to remind you that our expectations can change the nature of our biology, including our brains! Indeed, recent research suggests just fearing that you will get Alzheimer’s can potentially increase your chance of getting it by up to 60%.

Dr Leaf doesn’t offer any proof that “Our expectations change the nature of our biology” but she does allude to “recent research” which suggests that “just fearing that you will get Alzheimer’s can potentially increase your chance of getting it by up to 60%”. She doesn’t reference that either. She could be referring to the research from Yale which she alludes to later in her post, although that research by Levy and colleagues didn’t mention anything about the risk of Alzheimer disease increasing by 60 percent [18]. In fact, given certain methodological weaknesses, it didn’t conclusively prove that negative beliefs about aging did anything to the brain, but that’s a topic for another day.

Dr Leaf made several attempts throughout the rest of the blog to portray Alzheimer disease as a disease related to toxic thoughts and poor lifestyle choices. For example:

There is now a growing body of research that approaches the question of Alzheimer’s and the dementias as a preventable lifestyle disease, rather than a genetic or biological fault. More and more scientists are looking at Alzheimer’s and the dementias as the result of a combination of factors, including how toxic stress and trauma are managed, the quality of someone’s thought life, individual diets and exercise, how we can be exposed to certain chemicals and toxic substances, the impact of former head injuries, and the effect of certain medications.

That statement is just a big furphy. Yes, Alzheimer disease is the result of a complex interaction of genes and environmental factors. Yes, there is some evidence looking at the interactions of diet and exercise, environmental exposures and former head injuries (although there’s very mixed evidence for the role of brain trauma in Alzheimer disease. It’s not clear cut [19]). But there is no ‘growing body of research’ that claims Alzheimer disease is not strongly genetic or biological, and there’s certainly no real scientist dumb enough to call Alzheimers a “preventable lifestyle disease”.

The evidence is pretty clear, that there are very strong genetic factors for developing Alzheimer disease. Yes, some of them can be modified by environmental factors, but it’s foolhardy to claim that Alzheimer disease can be entirely prevented, based on the current evidence I outlined earlier. Dr Leaf is rushing in where angels fear to tread.

Dr Leaf’s baseless exaggerations don’t stop there.

It is therefore unsurprising that professor Stuart Hammerhoff of Arizona University, who has done groundbreaking research on consciousness and memory, argues that the kind of thinking and resultant memories we build impacts our cell division and can contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s and the dementias.

Dr Leaf includes a hyperlink which when clicked, takes you to this article: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/health/conditions/new-theory-targets-different-origins-of-alzheimers/article4210442/.

It’s not a scientific paper, but a newspaper article which is more than seven years old. The only thing it says about Professor Stuart Hameroff is this:

One of the co-authors, Stuart Hameroff at the Center for Consciousness Studies at the University of Arizona, has argued that microtubules may also be involved in consciousness.

That’s it. There’s nothing else in the article about Prof Hameroff at all, nothing to back up Dr Leaf’s wild claim that our thinking and our memories alters cell division and contributes to the development of Alzheimers and dementia. Dr Leaf is just confabulating.

Dr Leaf also claims that:

One of the many studies that have come out of this research, done by the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, showed dramatic improvement in patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and the dementias when they were put on an individualized lifestyle-based program that includes diet, exercise and learning.

Again, that’s a gross exaggeration. The “research” that Dr Leaf is alluding to is a paper written by Bredesen [20]. It’s a narrative paper which describes a total of ten cases. That’s it – just ten cases. That’s nowhere near enough information to draw even the weakest of conclusions, but it gets worse. The paper only gives a formal description of three patients and their treatments, the rest were listed in a table. So there is even less data to draw any definitive conclusions from. The other serious weaknesses of the paper were that the patients self-identified, and most of them didn’t have dementia at all, but instead had “amnestic mild cognitive impairment” or “subjective cognitive impairment”. In other words, they were a little forgetful, or they only thought they were forgetful. The one subject that did have Alzheimer disease continued to rapidly deteriorate in spite of the program.

If you took Dr Leaf at her word, you would think that this treatment program was working miracles and clearly proved that Alzheimer disease could be cured by lifestyle treatment. The study showed anything but.

Again, Dr Leaf is proving herself untrustworthy – either she knew that the study failed to demonstrate significant results and she was deliberately deceptive, or she didn’t understand that the results of the study were not conclusive, in which case she’s too ignorant to be treated as an expert.

In the same vein, Dr Leaf writes:

Another famous study, known as the “Nun Study,” followed a number of nuns over several years, showing that, although extensive Alzheimer’s markers were seen in their brains during autopsy (namely neurofibrillary plaques and tangles), none of them showed the symptoms of Alzheimer’s and the dementias in their lifetime. These nuns led lifestyles that focused on disciplined and detoxed thought lives, extensive learning to build their cognitive reserves, helping others and healthy diet and exercise, which helped keep their minds healthy even as their brains aged!

The hyperlink that Dr Leaf included was to a Wikipedia page which again, said nothing about the nuns who were apparently impervious to the effects of Alzheimers. It did say that

Researchers have also accessed the convent archive to review documents amassed throughout the lives of the nuns in the study. Among the documents reviewed were autobiographical essays that had been written by the nuns upon joining the sisterhood; upon review, it was found that an essay’s lack of linguistic density (e.g., complexity, vivacity, fluency) functioned as a significant predictor of its author’s risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease in old age. The approximate mean age of the nuns at the time of writing was merely 22 years. Roughly 80% of nuns whose writing was measured as lacking in linguistic density went on to develop Alzheimer’s disease in old age; meanwhile, of those whose writing was not lacking, only 10% later developed the disease.

As it turns out, lots of nuns did end up with dementia after all … well that’s awkward – the page that Dr Leaf used to try and support her argument actually directly contradicted her.

Wikipedia’s entry was supported by the original journal article in the research from Riley et al [21]. And after a bit of gentle trawling of the scientific literature, I also found this article from Latimer and colleagues which said, “Interestingly, our results show very similar rates of apparent cognitive resilience (5% in the HAAS and 7% in the Nun Study) to high level neuropathologic changes” [22].

So, sure, some nuns did indeed have some plaques and tangles without showing signs of the disease, but not 100 percent of them as Dr Leaf tried to make out. In reality, it was only 7 percent of them! And given what we know from the current research, plaques and tangles often precede clinical symptoms, so it may be that the nuns in question were on their way to cognitive impairment, but they hadn’t quite made it. Who knows. One thing’s for sure, the “lifestyles that focused on disciplined and detoxed thought lives” didn’t stop dementia affecting most of the nuns in the study.

Dr Leaf finishes off her post with what she thinks will help prevent Alzheimer disease. Given that she clearly doesn’t understand Alzheimer disease, we need to take what she advises with a large dose of salt. Let’s look at what Dr Leaf suggested and see if it lines up with actual research.

Research shows that education, literacy, regular engagement in mentally-stimulating activities and so on results in an abundance of and flexibility in these neural connections, which help us build up and strengthen our cognitive reserves and protect our brain against the onset of Alzheimer’s and the dementias.

Like everything in life, the more you use your ability to think, the more you get better at it and the stronger your brain gets!

Rating: Half-true

Education has a small positive benefit, but the research isn’t clear if that’s cause or correlation. So yes, stimulate your brain and see what happens. It might not help stave off Alzheimer disease, but at least it will make the journey interesting it nothing else.

What else can you do to prevent Alzheimer’s and the dementias, or help someone already suffering cognitive decline?

1. Detoxing the brain:

I have written extensively about the importance of detoxing the brain by dealing with our thought life in a deliberate and intentional way. Our minds and brains are simply not designed to keep toxic habits and toxic trauma; we are designed to process and deal with issues. If, however, we suppress our problems, over time our genome can become damaged, which will increase the potential for cognitive decline as we age. This is why it is important to build up a strong cognitive reserves AND live a “detoxing lifestyle”, which essentially means that you make examining and detoxing your thoughts and emotions a daily habit. We want to have good stuff in our brain, yes, but we don’t want the neurochemical chaos of a bad thought life affecting our healthy cognitive reserves!

Rating: BS (“Bad Science”)

This is Dr Leaf’s favourite pseudoscientific claptrap, her neurolinguistic-programming-voodoo-nonsense that has no scientific basis whatsoever. Skip it and move on.

2. Social connections:

Intentionally developing deep meaningful relationships can help build up our cognitive reserves against Alzheimer’s and the dementias – our brains are designed to socialize! Loneliness and social isolation, on the other hand, can seriously impact the health of our brains, making us vulnerable to all sorts of diseases, including ones associated with cognitive decline and the dementias …

Rating: Half-true

Loneliness has deleterious effects on health, but there’s nothing in the research to suggest that loneliness is a risk factor for Alzheimer disease. Like we discussed about education and mental stimulation before, I think you should make friends and enhance your social connections. There’s no guarantee that it will make any difference to your risk of Alzheimer disease, but it will make things fun and interesting at least.

3. Sleep:

Dr. Lisa Genova, a neuroscientist, wrote the book Still Alice (this was also made into a movie), which describes the impact of the early onset of Alzheimer’s. She believes that buildup of plaques and tangles associated with Alzheimer’s can be averted, since it takes about 10 to 20 years before a tipping point is reached and cognitive decline becomes symptomatic. We all build plaques and tangles, but it takes at least a decade for them to actually affect our ability to remember, so there is hope!

There are things we can do to prevent this buildup, and sleep is an important one. During a slow-wave, deep sleep cycle, the glial cells rinse cerebrospinal fluid throughout our brains, which clears away a lot of the metabolic waste that accumulates during the day, including amyloid beta associated with the dementias. Bad sleeping patterns, however, can cause the amyloid beta to pile up and affect our memory. Essentially, sleep is like a deep cleanse for the brain!

Rating: What?

Dr Leaf’s advice here isn’t necessarily BS, it’s just plain confusing as she takes two unrelated chunks of information and tries to conflate them.

I don’t know if Dr Lisa Genova is a neuroscientist, or if she thinks the build-up of plaques and tangles can be averted or not. The science as I outlined earlier in the post shows that the rise in plaques and tangles predate clinical symptoms, so you don’t know if you have them or not. If that’s the case, how can you hope to reverse them. Science is working on it, but it’s not there yet.

Irrespective, Dr Leaf doesn’t present any evidence to support her statement that sleep clears amyloid proteins. And neither is there any evidence that sleep has a significant impact on the development of Alzheimer disease.

I think it’s good general advice to try and get a reasonable amount of good quality sleep so you can wake up refreshed. Whether it changes your Alzheimer disease risk, who knows.

2. Diet:

We can now say with a good degree of certainty that consuming highly processed, sugar-, salt-, and fat-laden foods contributes to increased levels of obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke, allergies, autism, learning disabilities, and autoimmune disorders and Alzheimer’s! Some of the ways modern, highly processed and refined foods can contribute to Alzheimer’s and the dementias include added, highly-processed sugars, which cause your insulin to spike and the enteric nervous system of your gut to secrete an abnormal amount of amyloid protein. This will start destroying the blood-brain barrier, and can contribute to the formation of the amyloid plaques of Alzheimer’s disease. Some researchers now even refer to Alzheimer’s as type III diabetes!

Rating: Complete and utter BS

High sugar and high fat foods is certainly a contributing factor to obesity and to diabetes, and indirectly to cardiovascular disease and stroke. That’s where the intelligence in Dr Leaf’s statement comes to a grinding halt. The rest of it is just a stream of fictitious nonsense without any basis in reality.

The western diet does not contribute to allergies, and it’s scientifically impossible for it to contribute to autism since autism is a genetic condition which expresses itself during foetal development, and I am yet to see a foetus chow down on a cheeseburger. But wait, there’s more – learning disabilities, and autoimmune disorders too, and of course, Alzheimer disease. Who cares that there’s no definitive trials to clearly prove that Alzheimer disease is in any way connected to our diets.

But apparently it’s the evil sugar which causes insulin to make the gut nervous system secrete amyloid proteins which destroy the blood brain barrier. When you put enough medical terms in a sentence, you would fool about 99 percent of people. But looking past the random string of medical jargon, it’s clear that Dr Leaf is deluded. The structural damage in Alzheimer disease comes from the nerve cell’s poor lipid metabolism, most of which comes from a gene which codes for a lipid carrying protein. Lipids have nothing to do with sugar. Besides, who cares if the enteric nervous system secretes amyloid … the enteric nervous system is in the gut [23], not the brain. Even her inconsistencies are inconsistent.

Dr Leaf’s throw-away line at the end, “Some researchers now even refer to Alzheimer’s as type III diabetes!” is ignorant or intentionally misleading. We’ve already established that the name “Type 3 diabetes” referred to the fact that scientists have recognised a metabolic disease with overlapping molecular mechanisms shared between diabetes and Alzheimer disease, not that Alzheimer disease is a metabolic disorder. Alzheimer disease is not because of too much sugar or bad lifestyle choices.

5. Exercise:

There is extensive research on the importance of exercise as a preventative tool against Alzheimer’s and the dementias. A number of studies show that people who exercise often improve their memory performance, and show greater increase in brain blood flow to the hippocampus, the key brain region that deals with converting short-term memory to long-term memory, which is particularly affected by Alzheimer’s disease.

Rating: Plausible

I don’t know what the state of the research is, but the study discussed earlier in the post about lifestyle changes did show improvement in risk for those who exercised. And out of all of Dr Leaf’s pronouncements, at least this one has scientific plausibility.

Exercise promotes a growth factor in the brain called BDNF. BDNF does stimulate the growth of new nerve cell branches. Growth of new nerve cell branches results in improved mood. It’s not entirely implausible to think that it would help with new memory formation and an enhanced hippocampus.

How much it really prevents Alzheimer disease is not clear, but given that exercise is universally good for you, I think it should be first on the list, not the last.

Dr Leaf – in a tangle

So in summary, Alzheimer disease is a complex multifactorial disease with a number of factors that affect its development, some of which can be changed, while others cannot.

Dr Leaf doesn’t understand this. Her reading of the literature about Alzheimer disease is limited and skewed by her biased assumptions about toxic thinking and lifestyle. Sure, there are some risk factors for Alzheimer disease which may be related to lifestyle and which may be modifiable, but Dr Leaf has failed to synthesise that information into the broader understanding of Alzheimer disease.

So some of her advice is helpful. Most of it is not. If you’re concerned that you or a loved one might have early memory loss, please don’t listen to Dr Leaf – see a real doctor instead and get the right advice.

References

[1] Alzheimer’s A. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14(3):367-429.

[2] Area-Gomez E, Schon EA. On the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: The MAM Hypothesis. FASEB J 2017 Mar;31(3):864-67.

[3] Eid A, Mhatre I, Richardson JR. Gene-environment interactions in Alzheimer’s disease: A potential path to precision medicine. Pharmacol Ther 2019 Jul;199:173-87.

[4] Toepper M. Dissociating Normal Aging from Alzheimer’s Disease: A View from Cognitive Neuroscience. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;57(2):331-52.

[5] Dai MH, Zheng H, Zeng LD, Zhang Y. The genes associated with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Oncotarget 2018 Mar 13;9(19):15132-43.

[6] Cupples LA, Farrer LA, Sadovnick AD, Relkin N, Whitehouse P, Green RC. Estimating risk curves for first-degree relatives of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: the REVEAL study. Genet Med 2004 Jul-Aug;6(4):192-6.

[7] Nordestgaard LT, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Rasmussen KL, Nordestgaard BG, Frikke-Schmidt R. Genetic variation in clusterin and risk of dementia and ischemic vascular disease in the general population: cohort studies and meta-analyses of 362,338 individuals. BMC medicine 2018 Mar 14;16(1):39.

[8] Altmann A, Tian L, Henderson VW, Greicius MD, Investigators AsDNI. Sex modifies the APOE‐related risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Annals of neurology 2014;75(4):563-73.

[9] Larsson SC, Traylor M, Malik R, et al. Modifiable pathways in Alzheimer’s disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis. Bmj 2017 Dec 6;359:j5375.

[10] Rantanen K, Strandberg A, Pitkälä K, Tilvis R, Salomaa V, Strandberg T. Cholesterol in midlife increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease during an up to 43-year follow-up. European Geriatric Medicine 2014;5(6):390-93.

[11] Ott A, Stolk R, Van Harskamp F, Pols H, Hofman A, Breteler M. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology 1999;53(9):1937-37.

[12] Huang C-C, Chung C-M, Leu H-B, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a nationwide population-based study. PloS one 2014;9(1):e87095.

[13] de la Monte SM. Type 3 diabetes is sporadic Alzheimer׳s disease: mini-review. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2014;24(12):1954-60.

[14] Scarmeas N, Luchsinger JA, Schupf N, et al. Physical activity, diet, and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2009 Aug 12;302(6):627-37.

[15] Hu N, Yu J-T, Tan L, Wang Y-L, Sun L, Tan L. Nutrition and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. BioMed research international 2013;2013.

[16] Heymann D, Stern Y, Cosentino S, Tatarina-Nulman O, Dorrejo JN, Gu Y. The Association Between Alcohol Use and the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2016;13(12):1356-62.

[17] Wu YC, Lin YC, Yu HL, et al. Association between air pollutants and dementia risk in the elderly. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2015 Jun;1(2):220-8.

[18] Levy BR, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB, Slade MD, Troncoso J, Resnick SM. A culture-brain link: Negative age stereotypes predict Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Psychol Aging 2016 Feb;31(1):82-8.

[19] Kokiko-Cochran ON, Godbout JP. The Inflammatory Continuum of Traumatic Brain Injury and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Immunol 2018;9:672.

[20] Bredesen DE. Reversal of cognitive decline: a novel therapeutic program. Aging (Albany NY) 2014 Sep;6(9):707-17.

[21] Riley KP, Snowdon DA, Desrosiers MF, Markesbery WR. Early life linguistic ability, late life cognitive function, and neuropathology: findings from the Nun Study. Neurobiology of aging 2005 Mar;26(3):341-7.

[22] Latimer CS, Keene CD, Flanagan ME, et al. Resistance to Alzheimer Disease Neuropathologic Changes and Apparent Cognitive Resilience in the Nun and Honolulu-Asia Aging Studies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2017 Jun 1;76(6):458-66.

[23] Costa M, Brookes SJH, Hennig GW. Anatomy and physiology of the enteric nervous system. Gut 2000;47(suppl 4):iv15-iv19.